The New Orleans General Strike of 1892: Black Labor, Class Power, and the Unfinished Struggle for Liberation

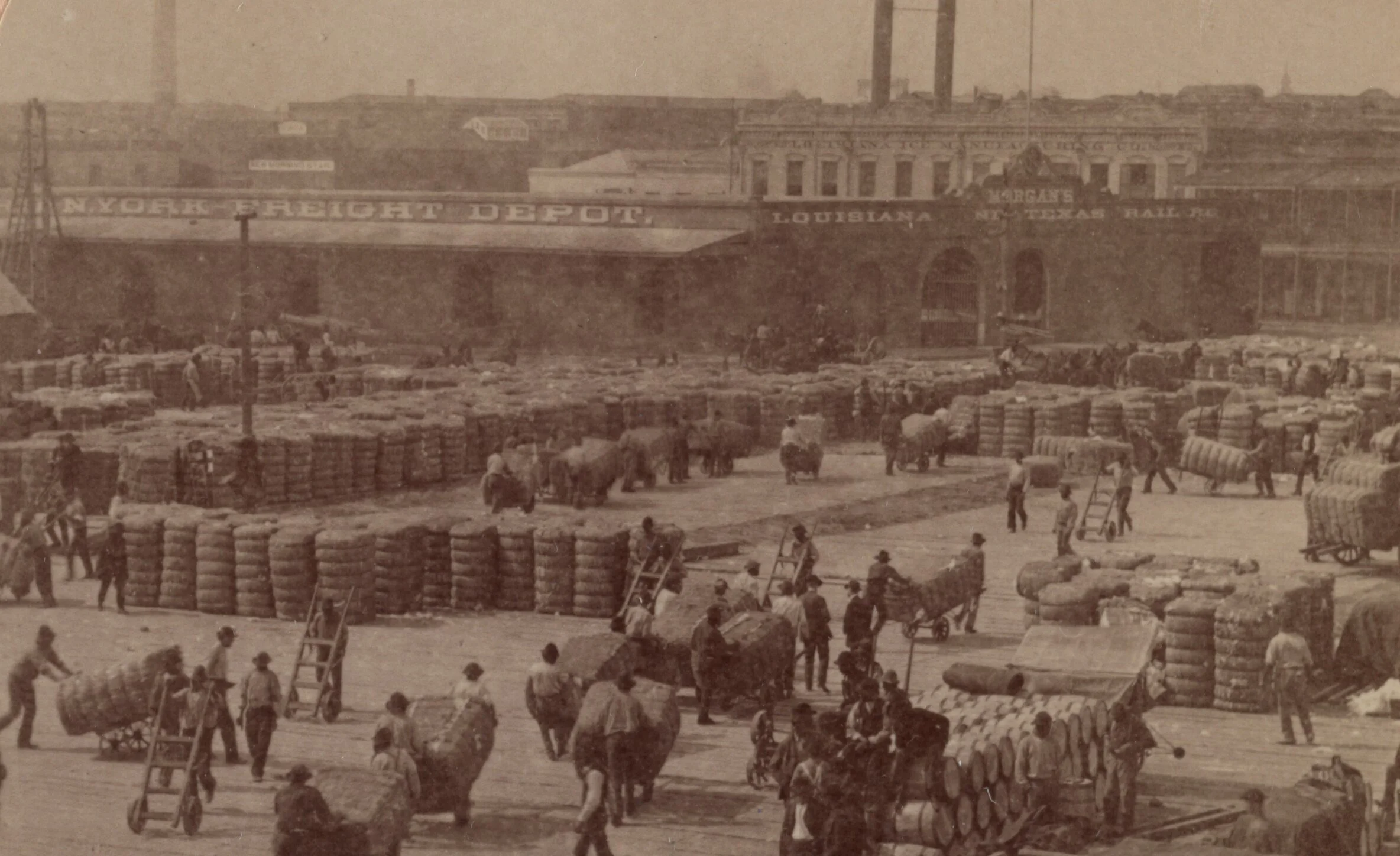

Photograph of tracking cotton from steamboat taken in 1891 in New Orleans (One year before the General Strike of 1892) The photo shows dockworkers moving cotton from steamboat to the distribution area.

The New Orleans General Strike of 1892 stands as one of the most extraordinary—and most deliberately forgotten—episodes in the history of the American working class. It was not merely a strike for wages or hours, but a confrontation between labor and capital that cut directly against the grain of white supremacy in the post-Reconstruction South. At its core was a radical proposition that Black and White workers, acting together as a unified class, could challenge both economic exploitation and racial domination. That proposition remains as dangerous to capital today as it was in 1892.

The Cotton Men’s Executive Council (1880)

The roots of the 1892 General Strike lay in earlier struggles led by Black workers on the New Orleans waterfront. In 1880, after a year of strikes initiated largely by Black longshoremen, waterfront unions consolidated into the Cotton Men’s Executive Council (CMEC). This body represented approximately 13,000 dockworkers across multiple trades and crafts and functioned as a unified negotiating front against the steamship companies and mercantile elite who dominated the port.

The CMEC was historically unprecedented in the Jim Crow South. It practiced formal biracial unionism, with equal representation for Black and White workers, shared hiring arrangements, and joint negotiation with employers to maintain standardized wages and work rules. Jobs were distributed across racial lines, undermining the employers’ preferred tactic of using Black labor as a reserve army to undercut white workers’ wages—and vice versa.

This was not racial liberalism; it was class strategy. Black workers, recently emancipated and brutally excluded from political power, understood that economic organization was essential to survival. White workers, facing capital’s relentless drive to cheapen labor, discovered that racial exclusion weakened their own bargaining power. In New Orleans, unlike much of the South, this material reality produced an interracial labor movement that briefly cracked the foundations of white supremacy.

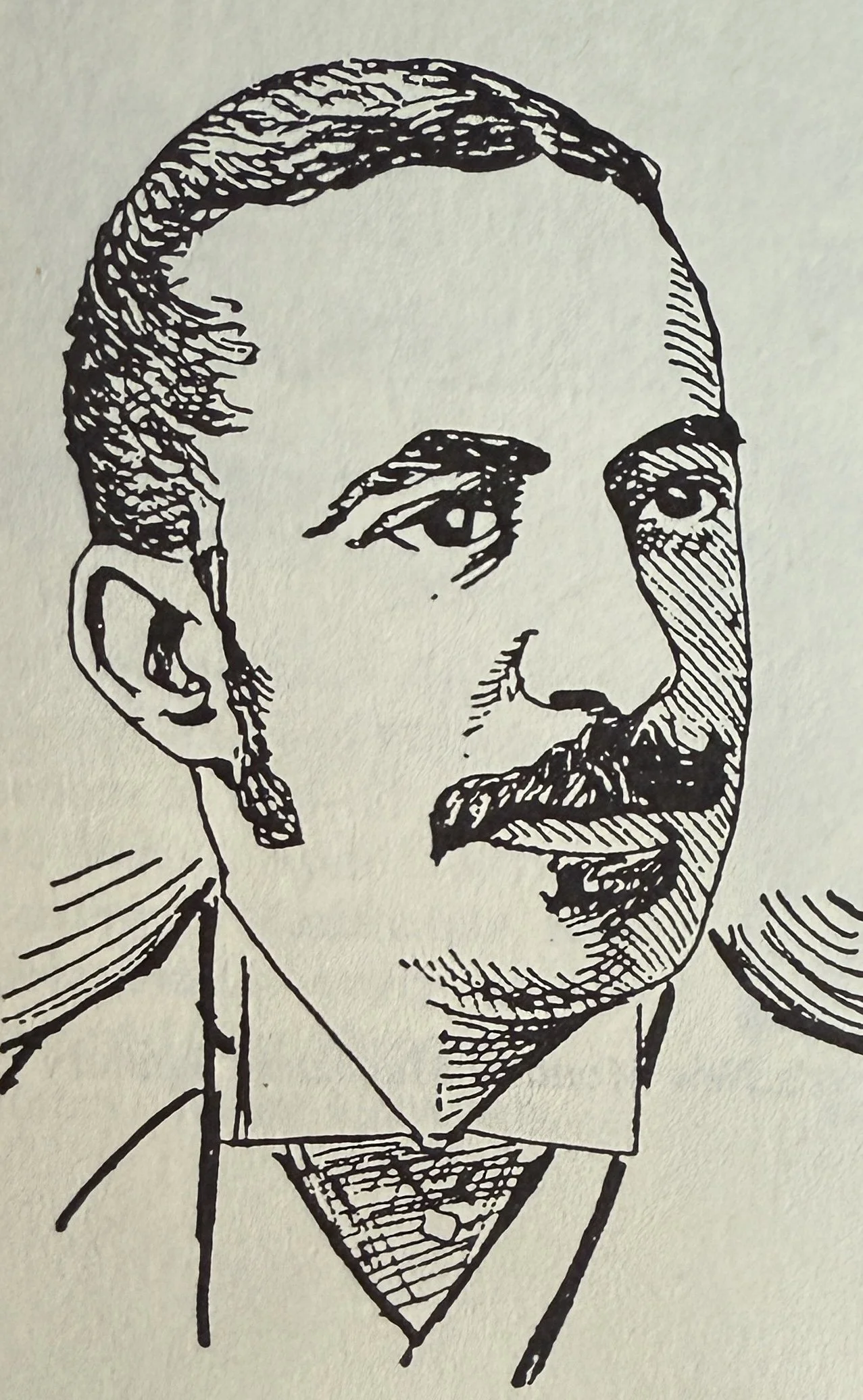

Among the CMEC’s most significant leaders was James E. Porter, a formerly enslaved man who rose to prominence as a longshoreman and labor organizer. Porter served in the Longshoremen’s Protective Union Benevolent Association, the CMEC, the Central Labor Union, the International Longshoremen’s Association, and later the Dock and Cotton Council. His leadership refutes the racist fiction that Black workers were passive or politically backward. In fact, formerly enslaved workers like Porter were often the most class-conscious militants in the Southern labor movement, precisely because they understood exploitation in its naked form.

The Central Trade and Labor Assembly (1881): Organizing Under Terror

James E. Porter

In 1881, New Orleans workers formed the Central Trade and Labor Assembly, a citywide federation drawing delegates from both Black and white unions. Its vice president was Black—an astonishing fact in a region where racial terror functioned as a tool of social control.

That same year, sixteen Black people were lynched in Louisiana. One man, accused of cattle theft, was tied inside the carcass of a slaughtered cow with only his head exposed, left for buzzards and crows to peck out his eyes. This was the social environment in which Black workers organized unions, marched publicly, and negotiated with employers.

In 1882, the Assembly celebrated its first anniversary with a parade expressing interracial unity. This act was not symbolic—it was defiant. Labor solidarity in New Orleans emerged not in the absence of racial violence, but in direct opposition to it. Black labor organizing was inseparable from Black survival.

The Workingmen’s Amalgamated Council and the Road to General Strike

By the early 1890s, New Orleans had become one of the most unionized cities in the South. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) was rapidly organizing across trades—streetcar operators, musicians, shoe clerks, carpenters, railway workers. By 1892, approximately 25,000 workers in the city were organized.

In May 1892, streetcar workers won a shorter workday, igniting a wave of confidence throughout the New Orleans labor movement. By summer, 49 unions affiliated with the AFL formed a new citywide coordinating body: the Workingmen’s Amalgamated Council. This council assumed leadership of what would become the most comprehensive general strike the South had ever seen.

The Triple Alliance and the Racism of Capital

The immediate spark came in November 1892 with the formation of the Triple Alliance of packers, scalesmen, and teamsters—between 2,000 and 3,000 Black and white workers striking together for:

A ten-hour workday

Higher wages

Overtime pay

Union recognition

A closed shop

Their negotiating delegations were explicitly 50 percent Black and 50 percent white, a direct challenge to the racial order of Southern capitalism.

The Board of Trade revealed its hand clearly. It expressed willingness to negotiate with the packers and scalemen—whose unions were majority white—but refused to recognize the all-Black teamsters union. This was racial capitalism laid bare—Black labor was acceptable only as cheap, unorganized, and subordinate.

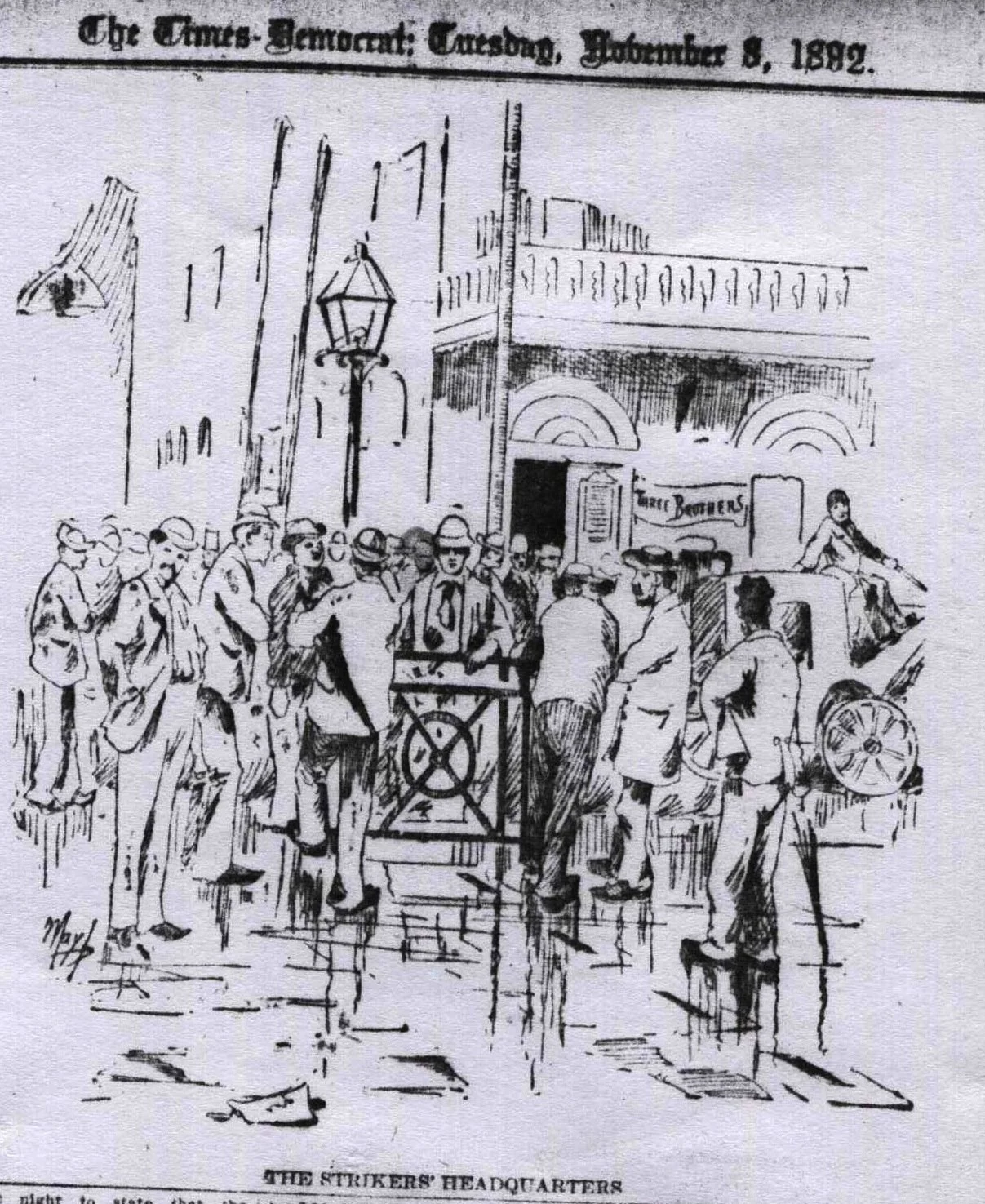

Workers gathered in front of the strike headquarters.

As the Triple Alliance unions walked out of negotiations, they encountered special pressures. Strikebreakers were recruited. Confrontations broker out; strikers and their families attacked strikebreaking teamsters, destroyed the wagons (“drays”), cut harnesses, and set free the horses.

The capitalist press responded to the Triple Alliances negotiation tactics with racial hysteria. The Times-Democrat warned white workers that they were under “Senegambia influence,” invoking colonial racist language to fracture class solidarity. This was divide-and-conquer in its purest form.

“The very worst feature, indeed, in the whole case seems to be that the white element of the labor organizations appear to be under the domination of Senegambia influence, or that they are at least lending themselves as willing tools to carry out Senegambia schemes.” (The New Orleans Times-Democrat, November 4, 1892).

The Workingmen’s Amalgamated Council appointed a Committee of Five, including James E. Porter, to negotiate with the New Orleans Board of Trade. As the ensuing talks plodded, labor’s mood took a decided turn toward a strike by all unions in the city, in support of both the Triple Alliance and the particular closed shop, wage, and hour demands of each trade. When employers stalled, the Committee of Five issued a declaration on November 4:

“The gauntlet has been thrown down by the employers that the laboring men have no rights that they are bound to respect and in our opinions the loss of this battle will affect each and every union man in the city, and after trying every honorable means to attain an equitable and just settlement, we find no means open but to issue this call to all union men to stop work and to assist with their presence and upon support…and how to the merchants and all others interested that the labor unions are united.”

The New Orleans General Strike (November 8–11, 1892)

The Workingmen’s Amalgamated Council called a general strike. Therefore, 25,000 workers walked off their jobs on November 8th. Virtually the entire city shut down. John M. Callahan, AFL organizer and Cotton Yardmen’s delegate, wrote to AFL president Samuel Gompers:

“There are fully 25,000 men idle. There is no newspaper to be printed, no gas or electric light in the city, no wagons, no carpenters, painters or in fact any business doing ... I am sorry you are not down here to take a hand in it. It is a strike that will go down in history.”

The strikers’ diversity was impressive. Unskilled dockworkers, shoe clerks, factory workers, and musicians all seemed determined to stay out until all demands were met. But there were exceptions: the cotton-handling unions on the levee—screwmen, longshoremen, and yardmen—remained at work, refusing to break newly negotiated contracts. In fact, no union with a contract stopped work. The recently victorious streetcar drivers did not join the strike. Clothing, hat, shoe, utility, and musicians’ organizations—“associations from the lower middle class occupations”—constituted the walkout’s backbone.

The Board of Trade appealed to Governor Murphy Foster to restore order with the state militia. The governor thereupon ordered a ban on street gatherings, warning of his readiness to call in the militia. With martial law pending, the strike was called off after three days.

Despite strikebreakers and threats of military intervention, there was no eruption of racial violence among workers. The strike ultimately collapsed not due to repression, but because cotton union leaders declined to fully shut down the port—the city’s economic jugular. Still, the Triple Alliance won the ten-hour day, higher wages, and overtime pay. A key demand was denied, however, and the workers did not achieve the closed shop.

That the Committee of Five had retreated before the massed force of management and government was apparently a conviction among many rank-and-file workers; moreover, the unions of four committeemen had continued working. The strike was not well planned, coordinated, or arranged with such key forces as the screwmen’s, longshoremen’s, and streetcar drivers’ unions. Nevertheless, the strike represented the apex of working-class power in the Southern United States, demonstrating that Crescent City unionism was remarkable not only for its racial accommodations. AFL president Gompers termed the effort a “very bright ray of hope for the future of organized labor”:

“Never in the history of the world was such an exhibition, where all the prejudices existing against the black man, then the white wage-earners…would sacrifice their means of livelihood to defend and protect their colored fellow workers. With one fell swoop the economic barrier of color was broken down.”

Legacy and Continuity: From 1892 to the New Deal

The spirit of 1892 did not die with the collapse of the general strike. Its lessons—interracial solidarity, militant organization, and the latent power of labor to halt capital—reappeared again and again in moments of heightened class struggle. In 1907, Black and white dockworkers once more shut down the entire port of New Orleans for three weeks, forcing employers to sign an unprecedented five-year contract. This victory confirmed what 1892 had already revealed in embryo: when labor acts collectively across racial lines, capital is compelled to retreat.

Nationally, it was mass strikes led by socialists, communists, and militant unionists that paved the way for the New Deal. The concessions of the 1930s did not emerge from enlightened governance, but from a sustained insurgency of the working class—one that was disciplined, radical, and often explicitly revolutionary.

The 1934 Minneapolis Teamsters Strikes

The pivotal 1934 Minneapolis Teamsters Strikes—there were three that year—were famously and successfully led by radical Communist organizers from Teamsters Local 574. These organizers were members of the Communist League of America (CLA), who applied revolutionary strategy to labor organizing. They developed innovative tactics such as flying pickets and a daily strike newspaper, forcing major concessions from employers and laying the groundwork for modern industrial unionism.

Socialists and Communist played a pivotal role in these strikes, leading Local 574 and organizing massive walkouts. Figures such as the Dunne brothers—Vincent, Miles, and Grant—and Carl Skoglund emerged as central leaders, transforming Minneapolis into a union stronghold and exerting national influence on the broader rise of industrial unionism.

The strike leadership emerged from radical political traditions, including the Communist Party (CP) and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The key organizers were members of the Communist League of America (CLA), the precursor to the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). These socialists championed industrial unionism, organizing unskilled workers and openly challenging the conservative craft-union orientation of the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

Employers and conservative AFL leaders, including Dan Tobin, denounced the organizers as “communists.” Yet the strikers, emboldened by their radical leadership, fought back fiercely during confrontations such as “Bloody Friday,”demonstrating immense working-class power. Led by these revolutionary socialists, the strike showed how disciplined, militant organizing could secure decisive victories, paving the way for the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and the explosive growth of unionism in the 1930s.

The West Coast Longshore Strike

The 1934 West Coast Longshore Strike also featured significant communist involvement, particularly through figures such as Harry Bridges, who led a radical rank-and-file movement on the docks. The Communist Party (CP) exerted major influence, especially in events like the San Francisco General Strike, where communist organizers helped guide the strike’s energy toward mass solidarity and worker self-organization against employer control.

Key Communist Party leaders, including Bridges himself, played central roles—particularly within the militant Albion Hall group, which organized dockworkers and articulated a vision of union democracy and class power. The strike was widely described as a “radical strike” and even a “festival of the oppressed,” driven by rank-and-file workers’ power, even though not all participants were Party members.

Throughout the 1930s, socialist activity surged within the labor movement, and the CP was deeply active in building influence. In response, the government and press targeted Bridges and other leaders, repeatedly attempting deportation on the basis of alleged communist ties. These attacks revealed the growing political tension between militant labor and the capitalist state.

The strike ultimately ended employer-controlled hiring, producing a resurgence of West Coast unionism. Communist influence remained strong in waterfront unions for decades. In essence, communists formed a crucial component of the militant leadership that shaped the 1934 strike, drawing strength from widespread worker dissatisfaction and channeling it into disciplined collective action.

The Toledo Auto-Lite Strike of 1934

The Toledo Auto-Lite Strike of 1934 likewise featured significant socialist involvement, particularly through the American Workers Party (AWP) and its affiliate, the Lucas County Unemployed League (LCUL). These organizations provided critical support, mass mobilization, and strategic leadership, linking striking workers with unemployed activists and sharply contrasting with more conservative union approaches.

The American Workers Party (AWP) was a socialist political party led by figures such as Louis F. Budenz, who played a central role in organizing the strike’s success and injecting it with radical, anti-capitalist energy. The Lucas County Unemployed League (LCUL), affiliated with the AWP, mobilized thousands of unemployed workers to reinforce picket lines, defy court injunctions restricting picketing, and build a massive, unified force against management.

AWP members offered strategic guidance, helping workers resist injunctions and counter management’s efforts to suppress the strike. This militant approach stood in clear contrast to the more “statesman-like” posture of the AFL leadership. The strike’s success—alongside the events in Minneapolis and San Francisco—highlighted the power of militant socialist leadership in challenging the status quo and clearing the path for broader industrial unionism under the CIO.

In essence, socialists and communists, provided the class-conscious leadership that transformed the Auto-Lite Strike into a major labor victory during the Great Depression.

The Flint Sit-Down Strike (1936–1937)

The Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1936–1937 also saw deep involvement from the Communist Party (CP) and the Socialist Party (SP). Communist militants such as Wyndham Mortimer, a vice president of the United Auto Workers (UAW), played a decisive role in the organizing campaign that confronted General Motors. Mortimer was instrumental in deep shop-floor organizing and in advancing the strategy of direct confrontation with corporate power.

Socialist organizer Genora Johnson Dollinger led the Women’s Emergency Brigade, providing critical protection for strikers and emphasizing the indispensable contributions of socialist and communist activists. Another key figure, Robert Travis, a UAW organizer, worked alongside a militant leadership that included CP and SP members.

Many union militants elected to strike committees—including the so-called “mayor” of the occupied plants—were Communist Party members. These committees organized self-defense, political education, and healthcare within the plants. The CP proved an essential ally, listening to workers’ demands and assisting them in achieving industrial unionism, particularly during the strike’s early and most vulnerable stages.

The strike benefited from the era’s Popular Front, in which radicals from diverse socialist and communist traditions collaborated within the UAW to build durable working-class power. The Flint Sit-Down Strike was a complex and collective movement in which Communist and Socialist activists were vital organizers, shaping the success of the sit-down tactic and securing broad support from the surrounding working-class community.

Radical Labor and the Road to Reform

As we read above, throughout the labor movement of the early twentieth century, organizations such as the Communist Party USA, the Socialist Party, and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) played decisive roles in organizing interracial unions, defending Black workers, and forcing concessions from capital. The New Deal reforms that followed were not gifts from above, but concessions extracted under pressure, made possible by decades of militant struggle rooted in revolutionary traditions.

The New Deal: Victories and Limits

The New Deal did not emerge from benevolence or moral awakening among political elites. It represented a series of concessions wrested from capital through mass struggle, forced into existence by a decade of strikes, factory occupations, unemployed mobilizations, and the growing influence of socialist and communist organizing throughout the United States. Faced with the prospect of social breakdown and sustained working-class insurgency, the ruling class chose reform not out of generosity, but as a strategy of preservation.

One of the New Deal’s most consequential achievements lay in the realm of labor rights and union power. For the first time in U.S. history, labor unions received formal legal recognition. The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, commonly known as the Wagner Act, enshrined the right of workers to organize and bargain collectively while prohibiting a range of unfair labor practices by employers. To enforce these rights, the federal government created the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), tasked with overseeing union elections and adjudicating labor disputes. These measures enabled the explosive growth of industrial unions, particularly under the banner of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), and significantly strengthened workers’ leverage through federally protected organizing.

The New Deal also reshaped the conditions of work itself. With the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, the federal government established a national minimum wage, mandated overtime pay for work beyond forty hours per week, and codified the 40-hour workweek as a legal standard. The Act imposed restrictions on child labor and introduced basic federal workplace standards, curbing some of the most egregious forms of exploitation that had long defined American industrial capitalism.

In the sphere of social insurance and economic security, the New Deal marked a decisive rupture with the laissez-faire orthodoxy of the nineteenth century. The Social Security Act of 1935 created a system of old-age pensions, survivors’ benefits, and disability protections, the latter expanded in subsequent decades. It also established unemployment insurance, providing income support for workers displaced by economic downturns, and introduced aid to dependent children, later known as AFDC and now TANF. Together, these programs represented the first national acknowledgment that economic insecurity was not a personal failure, but a structural feature of capitalism itself.

Equally transformative were the New Deal’s public employment programs, which put millions to work at a time of mass unemployment. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) provided jobs for young men while undertaking large-scale environmental restoration. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) employed millions more in construction, education, and public services, while also funding artists, writers, musicians, and theater workers—an implicit recognition that cultural labor is socially necessary labor. The Public Works Administration (PWA) focused on large-scale infrastructure, reshaping the physical landscape of the nation through dams, schools, hospitals, and public buildings. The list of New Deal initiatives is extensive, and a full accounting demands sustained independent study to grasp the breadth and scale of the legislation enacted during this period.

These reforms were funded in part by steeply progressive taxation, including top marginal income tax rates that exceeded 90 percent during the 1940s and 1950s—a fact that sharply contradicts contemporary claims that robust social provision is fiscally impossible. Yet even as the New Deal expanded the social wage for millions, it did so within rigid racial boundaries.

The New Deal was not without profound and structural limitations. Black workers were systematically excluded from many of its most important protections, particularly agricultural and domestic laborers—occupations disproportionately held by African Americans in the Jim Crow South. These exclusions were not incidental but the product of deliberate political compromises with segregationist lawmakers, revealing the racial limits of social democracy under capitalism.

Federal housing policy entrenched segregation rather than dismantling it. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA)promoted racial apartheid by refusing mortgage insurance in Black neighborhoods and enforcing racial covenants, helping to institutionalize redlining and intergenerational dispossession. Programs such as the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and the CCC operated segregated facilities or favored white workers, while local administration routinely embedded racial bias. The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) frequently channeled aid to white landowners, who then withheld benefits from Black sharecroppers, intensifying displacement and poverty in the rural South.

The New Deal thus stands as a contradictory legacy: a testament to the power of organized labor and mass struggle to force concessions from capital, and a reminder that reforms won under capitalism are always partial, uneven, and contested, shaped by the prevailing balance of class forces and constrained by racial hierarchy. It stabilized the system, alleviated widespread suffering, and expanded working-class power—while simultaneously reproducing exclusions that would require further struggle to confront and dismantle.

War, Anti-Communism, and the Taft–Hartley Counterrevolution

The socialist and communist influence within the U.S. labor movement that had helped force the New Deal into existence did not go unanswered. Even before the end of World War II, the ruling class was preparing its counteroffensive. The scale of working-class power demonstrated in the 1930s—factory occupations, mass strikes, interracial unionism, and the growth of explicitly socialist leadership within unions—posed an existential threat to American capitalism. That threat was magnified by events abroad.

The Soviet Union’s transformation from a backward, semi-feudal agrarian society into an industrial powerhouse capable of defeating fascism shattered the ideological foundations of Western capitalism. The USSR bore the overwhelming burden of World War II, destroying the bulk of the Nazi war machine and sacrificing more than 27 million lives in the process. This was not merely a military victory; it was a civilizational challenge. It proved that socialism could mobilize labor, plan production, and defeat the most advanced forms of capitalist barbarism. For Western capital, this reality was intolerable.

The postwar response was the Cold War—a coordinated campaign of ideological warfare, state repression, and legal restructuring designed to break the militant labor movement at home. At the center of this offensive stood the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947, a deliberate counterrevolution against the gains workers had won through mass struggle. Far from a neutral “labor reform,” Taft–Hartley was explicitly designed to target socialists and communists—the most disciplined, class-conscious, and interracial elements of the labor movement.

Through its so-called “non-communist” loyalty oaths, Taft–Hartley forced union officers to swear they were not members of the Communist Party and did not support revolutionary change. This provision was not about democracy or national security; it was a purge mechanism. Unions that refused to expel socialist and communist leadership were denied access to the National Labor Relations Board, stripping them of legal protection and effectively criminalizing their organizing. In this way, the state intervened directly to decapitate militant unions, split rank-and-file organizations, and remove leaders committed to class struggle.

Equally central to Taft–Hartley was its systematic dismantling of solidarity. The Act outlawed the closed shop, undermining one of labor’s most powerful tools for maintaining unity and preventing employer divide-and-rule tactics. Through Section 14(b), it authorized so-called “right-to-work” laws, deliberately designed to weaken unions financially and organizationally—particularly in the South, where capital sought to preserve a low-wage, racially stratified labor regime. Louisiana and the broader South were thus locked into their role as anti-union strongholds by federal design, not historical accident.

Most decisively, Taft–Hartley functionally outlawed the general strike. While the Act does not use the phrase explicitly, its combined prohibitions on secondary boycotts, sympathy strikes, jurisdictional strikes, and political strikes made cross-industry, citywide, or nationwide work stoppages illegal in practice. The president was granted sweeping authority to impose federal injunctions and enforce “cooling-off” periods whenever a strike threatened the so-called “national health or safety”—a vague standard that ensured any mass disruption of capital could be forcibly suppressed. The very tactic that had shut down New Orleans in 1892, and later fueled the great strikes of the 1930s, was rendered illegal under federal law.

In sum, Taft–Hartley was not simply an adjustment to labor law; it was a class weapon. It criminalized the strategies of mass solidarity, purged communists and socialists from union leadership, weakened interracial unionism, and restored employer dominance under the banner of anti-communism. It marked the decisive turn from concession to containment, ensuring that the militant traditions represented by 1892 would be remembered as history rather than permitted as living practice.

Black Liberation and the Road Forward

The New Orleans General Strike of 1892 teaches a lesson the ruling class has desperately sought to erase—Black liberation is not peripheral to our struggle for socio-economic justice—it is central to it. Wherever Black workers have led, the labor movement has been strongest. Wherever they have been excluded, labor has been defeated. The unfinished struggle of 1892 is not mere history—it is a mandate for action today.

The Necessity of a General Strike Today: Illegality, Legitimacy, and the Crime of Capital

If 1892 teaches us anything, it is that legality is not a measure of justice. The strike was condemned by the press, threatened by the state, and opposed by the city’s mercantile elite—yet history vindicates the workers, not their oppressors. Today, as in 1892, the ruling class invokes the law to discipline labor while committing social crimes on a mass scale. The question is not whether a general strike is legal, but whether continued submission is tolerable.

The true crime of our era is not collective work stoppage—it is the systematic deprivation of human needs in the name of profit. In the wealthiest society in human history, millions are denied universal healthcare, transforming illness into financial catastrophe and death into a class outcome. The federal minimum wage has been frozen since 2009, a deliberate act of class warfare transferring trillions from labor to capital. Public education is starved, privatized, and hollowed out, while union-busting—once shameful—has been normalized and legalized.

Housing, the most basic human necessity, has been surrendered to speculation. Rent hikes, mass displacement, and the disappearance of affordable, dignified housing are not accidents—they are predictable outcomes of treating shelter as an asset rather than a right. In cities like New Orleans, working people are coerced into car ownership by capitalist urban design—incomplete streets, non–ADA-compliant sidewalks, inadequate crosswalks, dangerous roads, absent protected bike infrastructure, and an underfunded, unreliable public transit system. This is not mere inconvenience—it is a hidden tax on the working class, enforced through geography.

The United States remains virtually alone among advanced economies in offering no guaranteed paid vacation. This is not austerity—it is theft of life itself. A humane society would guarantee not 2 weeks, but a month of paid rest. A four-week paid vacation, universal and unconditional, is not utopian; it is the rational redistribution of the immense surplus produced by modern labor. Similarly, guaranteed income is not charity but partial restitution for centuries of exploitation—especially for Black workers, whose super-exploitation built the primitive accumulation of American capitalism.

Why a General Strike—and Why It Must Be Total

These demands will not be granted through polite appeals, electoral rituals, or fragmented workplace actions. History is unequivocal—only mass, coordinated disruption has ever forced capital to concede. The New Deal itself was not a gift from enlightened politicians; it was wrested from the ruling class by the credible threat of systemic breakdown—by strikes, occupations, and socialist organization.

A general strike today must be broader and more inclusive than any in U.S. history. It must unite:

Union and non-union workers

Public and private sectors

Waged and 1099 workers

Documented and undocumented workers

Industrial, service, care, cultural, and informal labor

In short, all who sell their labor—or are denied the right to live without selling it—must be included. Capital already treats the working class as a single mass when extracting surplus value; labor must respond in kind.

The illegality of such a strike under laws like Taft–Hartley is not incidental—it is proof of its necessity. These laws were designed precisely to prevent the kind of interracial, cross-sector solidarity that defined New Orleans in 1892. They criminalize unity because unity works. They outlaw general strikes, prohibit solidarity actions, and target socialists and communists—the very organizers who historically brought labor together to wield power.

We ally with General Strike U.S... Research shows that for a general strike to be successful, only 3.5% of the population is needed to have a massive impact on shutting down society. Given the population of the United States, this would require approximately 11 million workers walking off their jobs until our demands for a Third Reconstruction are met.

Learn more about General Strike U.S.. here, and consider signing a strike card.

From 1892 to the Present: Continuity of Struggle

The workers of New Orleans understood that power does not flow from the law; the law flows from power. They understood that Black liberation and class liberation were inseparable, and that only collective action could overcome both racial domination and economic exploitation. Their struggle remains unfinished—not because it failed, but because it was interrupted.

A general strike today would not be an act of chaos, but an act of collective self-defense. It would assert that healthcare, housing, mobility, education, leisure, and dignity are not privileges to be purchased, but rights to be enforced. It would declare, as the workers of 1892 declared, that labor creates all wealth—and therefore labor must rule.

The lesson of 1892, the repression of Taft–Hartley, and the decades of deferred justice since are not abstract history—they are a call to action. The ruling class has always responded to worker power with violence, legal restrictions, and ideological warfare, yet every concession, from the ten-hour day to Social Security, was wrested from capital by organized labor. Today, as then, the law serves capital, not justice. It is time to turn this history into action—to organize, to unite, to strike across industries, sectors, and borders of legality. A universal general strike—uniting Black, Brown, and White, documented and undocumented, service, industrial, care, and cultural workers—is not merely a tactic; it is the necessary assertion that labor, which produces all wealth, must determine how that wealth is used. The time to act is now. History demands nothing less!

-Eric Gabourel

The author giving a presentation of the New Orleans General Strike of 1892 at a PSL teach-in.

Consider joining the PSL action network here.