Toward A Third Reconstruction: Exploring Cooperative Economics with Black Men Build - Bvlbancha

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to everyone who participated in our community engagement ride on Monday evening. The bicycle ride was a collaboration between Critical Mass Nola and Black Men Build - Bvlbancha. Black Men Build is a national organization built on the principles of Black liberation. Bvlbancha is the Indigenous name for what was renamed New Orleans to honor Philip II, the Duke of Orléans, when the Louisiana capital was established here in 1718.

On the heels of Black Men Build’s maroon camp, we collaborated to explore the theme of maroonage and the practice of cooperative economics by escaped slaves in the antebellum period, as a blueprint for escaping the wage-slave economy of today. As discussed on our bicycle ride from the 5th Ward to the 9th Ward, the solidarity economy is not based on competition, but on cooperation within our community. Cooperative economics is less concerned with the profit motive; its primary concern is that the economy should be planned to meet the needs of the people and the health of the planet.

There are many ways that cooperative economics can manifest in our neighborhoods: worker-owned cooperatives, credit unions, tool libraries and bike repair co-ops, mutual aid networks, housing cooperatives, energy cooperatives, and neighborhood repair collectives based on democratic centralism. Our conversation leaned more toward community-supported agriculture (CSA) as we visited three community gardens on the bike ride.

At the start of the ride, we reflected on Juan San Malo and the maroon haven he created—Terre Gaillard—in St. Bernard Parish during the 1780s. In Terre Gaillard, Juan San Malo and other escaped slaves grew their own produce, caught seafood and wild game, and carved vats and troughs to sell to plantation owners.

Juan San Malo created a cooperative economy in Terre Gaillard that existed alongside—and in defiance of—the slave economy they had escaped. San Malo used the money he earned from selling his carvings to amass gunpowder and arms. The goal of the maroons was revolt and the overthrow of the slave economy.

But in the process of planning to overthrow the slave system, they were also creating—building the cooperative system they wanted to see in place of the cutthroat slave economy based on surplus value and capital extracted from enslaved labor.

Slavery built the prosperity of New Orleans, yet the descendants of those who built it still do not share in what they created. Juan San Malo was ultimately captured and lynched in Place d’Armes (now Jackson Square) on June 19, 1784.

He left behind a legacy—one that compels us to create a similar cooperative economy, independent from our current economy, rigged by billionaires and still based on surplus value extracted from the working class. The billionaires have structured an economy devoid of robust public services, built instead on the concentration of wealth into the hands of the few; real estate treated as an investment asset rather than meeting human need; privatization of all industries so they can be commodified; imperialism (forced expansion of their industries into other countries through military might); and a social safety net for billionaires when they fail.

As exemplified through the subprime loan scheme and the recession of 2008, the billionaires and the private banks they control were bailed out of bankruptcy with our tax dollars. When working-class people fail in this economy, there is no bailout. We must live through our bankruptcy—if we can claim it—in an economy of low wages, high rents, inflated grocery prices, and crippling interest rates.

The First Reconstruction: After The Civil War (1965-1877)

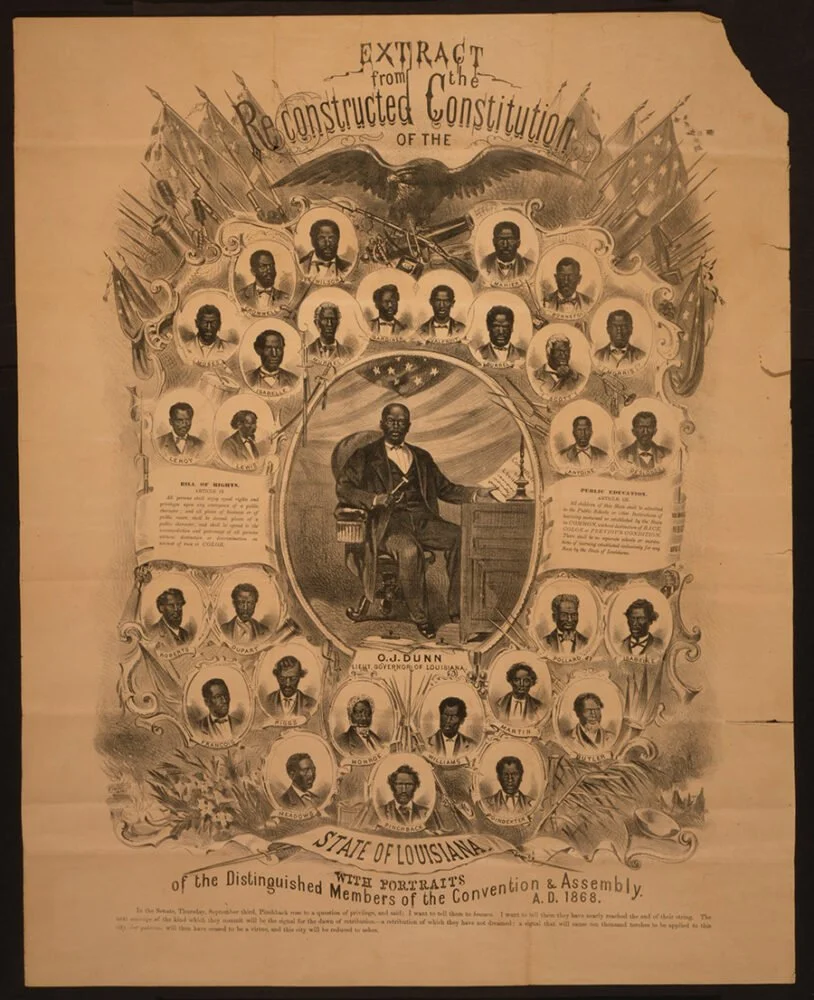

Poster with text from the state constitution depicting Black leaders in Louisiana during Reconstruction, 1868.

Slavery was crucial both to pre-capitalist primitive accumulation and to capitalist growth in the United States. When the enslaved entered the Civil War, they transformed it into a revolutionary war, propelling significant Black involvement at the beginning of Reconstruction.

A new world had emerged, rich with possibility. Under the auspices of Reconstruction came the promise of land redistribution: formerly enslaved people were to receive “40 acres and a mule.” The monopoly of the plantation owners was supposed to be broken up — but what came to fruition were broken promises.

At the start of Reconstruction, 50% of the delegates at the constitutional convention in Louisiana were Black. Radical Reconstruction brought integrated public schools, and, after the audacious protest of Joseph Guillime, public transit became desegregated.

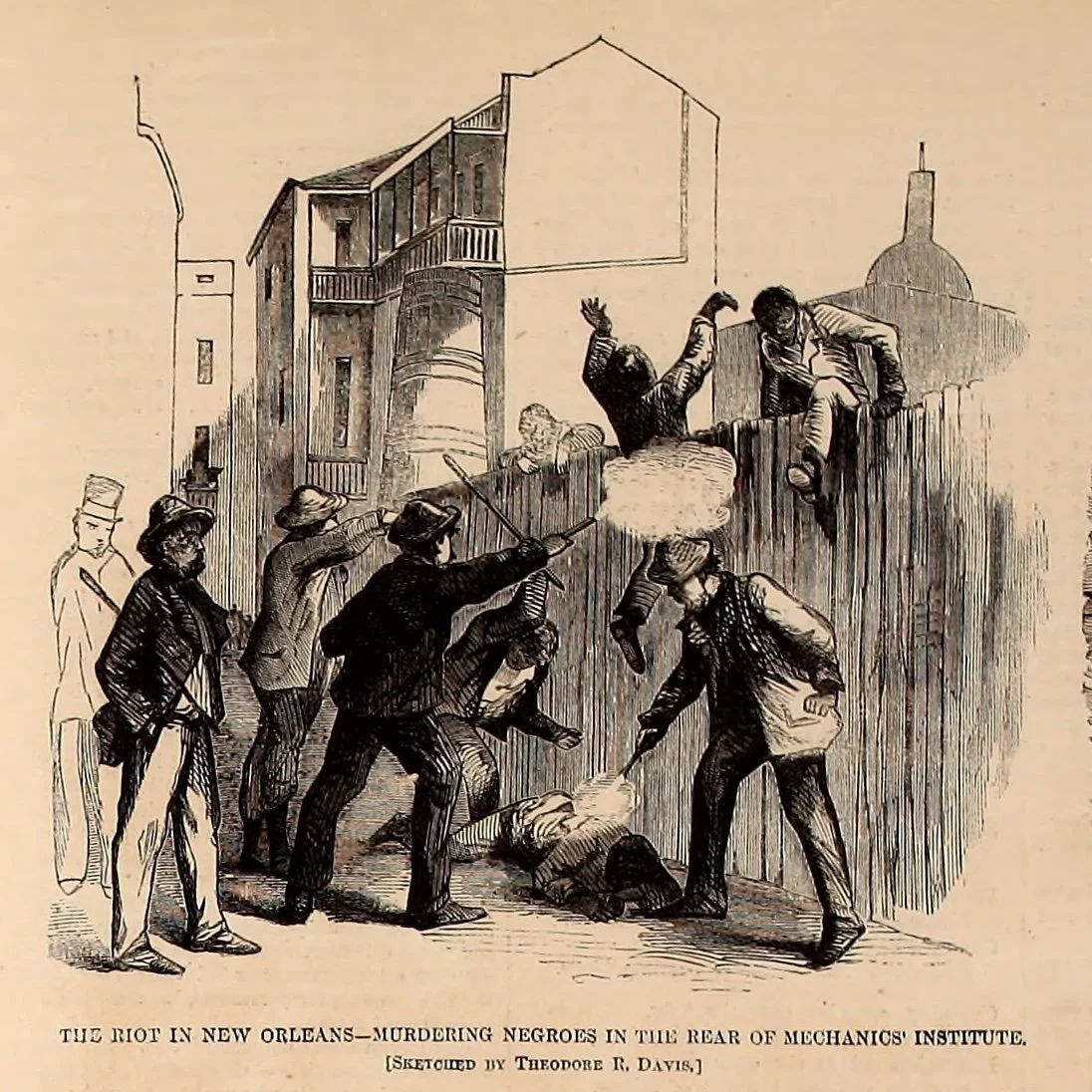

"Murdering Negroes in the rear of the Mechanics' Institute" – Sketched by Theodore R. Davis (Harper's Weekly, August 25, 1866)

While such advancements and plans for land reform were underway, white supremacist organizations mobilized against any progress for formerly enslaved people. In 1866, during the reconvening of the Louisiana constitutional convention to advocate for the right to vote, the Crescent City White League committed a massacre at Canal and Baronne Streets, killing an estimated 130 Black people.

Beyond the fight for the vote, working-class organization intensified. Strikes became a regular feature of life. Scribner’s Monthly lamented that labor had come under the sway of the “senseless cry against the despotism of capital.” In New Orleans, the white elite feared Louisiana’s constitutional convention of 1867 would be dominated by a policy of “pure agrarianism” — that is, attacks on property.

The unease of the landowning classes with the radical agitation among newly organized laborers, and the radical wing of the Reconstruction coalitions, was only heightened by the Paris Commune in 1871. For a brief moment, the working people of Paris grasped the future and established their own rule, displacing the propertied classes. It was an act that scandalized ruling elites around the world and, in the United States, stoked fears of the downtrodden seizing power.

The fear that the ideas of the Paris Commune could spread among the working class of the South — that they could erect barricades and take control of society — agitated plantation owners into mounting a counter-revolution. This demagoguery against the social contract of the First Reconstruction undermined its promises before they could be realized. The plantation owners maintained their monopoly, control of the economy, and privilege. The formerly enslaved were left to endure the violence of white supremacy, exploitation, and Jim Crow segregation.

The First Reconstruction was an unfinished revolution. Enslaved people had been the property of the plantation owners; in that regard, billions of dollars in wealth were stripped from the plantation monopoly. If it happened then, it can happen again.

The Second Reconstruction: The Civil Rights Revolution (1955-1968)

The 1940s was the “American Century.” The United States rose to global dominance in the post–World War II era, wielding significant political, economic, and cultural influence. This period saw the U.S. emerge as the world's leading economic power, experience rapid technological advancements, and play a crucial role in shaping international affairs.

Portraying itself as a beacon of light to the nations, the U.S. entered into a Cold War with the Soviet Union in 1947. It framed this struggle as a battle between freedom and totalitarianism, yet many of the nations it opposed were in the process of freeing themselves from monarchy, colonial rule, and the domination of foreign markets. At the same time, many of America’s own citizens were living under apartheid conditions and treated as second-class citizens.

It was in this atmosphere that the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott began. As with the First Reconstruction, the same entrenched powers—those controlling monopolies, wealth, and privilege—pulled out every stop to halt the advancement of social justice. McCarthyism also weakened the early civil rights movement by purging leftist voices that could have strengthened its vision and strategy.

The white ruling class did not expect the Black freedom movement to reemerge with such force until the Montgomery Bus Boycott shook the nation. During this period, Mississippi took center stage. In 1960, 70% of the state’s Black population lived in rural areas, most as sharecroppers still laboring in cotton fields. Sharecropping often trapped families in a cycle of debt—landowners controlled prices at plantation stores, and sharecroppers frequently had to borrow money for supplies, ensuring they could never earn enough to achieve independence.

The census of the era shows that most Black Mississippians lived below the federal poverty line, and their schools were drastically underfunded. Only 7% of Black students graduated from high school, and just 7% of Black adults were registered to vote. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and “understanding clauses” about the constitution were all used to keep them disenfranchised.

In 1961, civil rights groups in Mississippi united to form the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) to coordinate and amplify their efforts. Member groups included the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the NAACP, and local grassroots networks. COFO focused on voter registration, freedom schools, and building the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP)—an alternative to the segregationist Democratic Party of Mississippi.

To prepare communities for the vote, they organized the Freedom Vote, a mock election to show Black Mississippians the mechanics and power of the ballot. When the MFDP was officially formed, it demanded more than the right to vote—it called for land reform, guaranteed access to electricity, heating, running water, and free mass transit.

On August 6, 1964, the MFDP held a state convention with Ella Baker as keynote speaker. Two thousand five hundred people attended, electing 68 delegates to travel to Atlantic City for the Democratic National Convention. They demanded to be recognized as the true representatives of Mississippi’s people. President Lyndon B. Johnson had just signed the Civil Rights Act, but the national Democratic Party refused to seat them.

The MFDP exposed the hypocrisy of the two-party system. While many activists see electoral politics in our two party system as a dead end, engaging them could reveal its corruption and mobilize new forces for change. That’s exactly what the MFDP did.

At the convention, delegates worked both inside and outside, distributing literature and telling their stories. Their spokesperson, Fannie Lou Hamer, gave a nationally televised testimony about being denied the right to register and the brutal reprisals she faced. Johnson, fearful of her impact, interrupted the broadcast with an impromptu press conference—but the move backfired. Her full speech aired that evening to an even larger audience.

Johnson offered a “compromise”: the MFDP could have two at-large delegates the following year. The MFDP rejected the offer. They didn’t win official seating, but they proved that poor and working-class people could organize power, laying the groundwork for the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The struggle continued to face violence—Bloody Sunday on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the beating death of Reverend James Reed, and the roadside murder of Viola Liuzzo by Klansmen. One of Liuzzo’s killers, Gary Thomas Rowe, was both a Klan member and an FBI informant, known to have participated in earlier violence, including the Birmingham church bombing and assaults on Freedom Riders.

LCFO political ad from 1966 against the Democratic Party of Alabama

The Democratic Party considered the MFDP too radical, particularly under leaders like Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), who was also involved in the Lowndes County Freedom Organization—from whom the Black Panther Party would adapt their symbol— opposed the Vietnam War and supported African independence movements.

The Legacy of Cooperative Gardens

One of the enduring legacies of this movement was the creation of cooperative farms and gardens as tools of economic self-determination. In 1967, Fannie Lou Hamer founded the Freedom Farm Cooperative in Sunflower County, Mississippi. It began with 40 acres purchased through donations and grew to over 600 acres. The farm provided food, livestock, and housing assistance, and also ran a “pig bank” program that lent families breeding pigs to help them generate their own food and income. All proceeds were reinvested directly into the community.

Similar efforts emerged across the South. In Georgia, New Communities, Inc., founded in 1969 as a land trust and farm cooperative, became one of the largest Black-owned tracts of land in the country. Though they lost their original land in the 1980s due to discriminatory lending by the USDA, the organization won a historic settlement in 2009 and continues to operate today.

The Poor People’s Cooperative (PPC)—sometimes called the Poor People’s Corporation—grew out of the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968, led by the SCLC after Dr. King’s assassination. The PPC supported worker-owned cooperatives in the Deep South, offering training, financial aid, and market access for small-scale manufacturing, farming, and crafts. These were designed to be self-sustaining and democratically run, challenging both racial and economic oppression.

From gerrymandering to attacks on diversity, equity, and inclusion, the Second Reconstruction—like the First—has faced fierce backlash. But as radicals from the civil rights movement understood, the root of the struggle lies in the economy.

The Third Reconstruction (The Present Moment-The Future)

The Poor People’s Campaign was one of the failed struggles waged at the end of the Second Reconstruction. Instead of fighting for gains that have failed us, we can look to the Poor People’s Campaign to gleam some key gains to focus on. In our pursuit of a Third Reconstruction, we must begin now to create the economy we want to see. We know that the same forces that own monopolies, control the economy, and cling tightly to their privilege—namely the billionaire class—will push back against our efforts to free ourselves from their domination.

At the end of his life, Dr. King confessed that his dream had turned into a nightmare. After deep analysis and soul-searching, he admitted that some of his earlier optimism was superficial and had to be tempered with reality. King concluded that there must be a restructuring of the very architecture of our society. True and lasting change, he argued, could not exist until we confront the “triplets of evil” in U.S. society: racism, economic exploitation, and militarism. These three are inextricably interconnected; one cannot exist without the others.

For King, civil rights alone were not enough. He believed we would never be truly free until we had economic rights. Part of the Poor People’s Campaign was organizing for an Economic Bill of Rights—one that would require the economy to be planned by the working class to meet the needs of the people and protect the health of the planet.

The current economic system is controlled by billionaires and must be reorganized. The billionaire class fears people having Social Security, universal healthcare, and free public universities because they know that once working-class people have access to these basic human rights, they will get a taste of freedom and demand more.

The tragedy is that their addiction to wealth blinds them to the fact that they could still be wealthy while paying higher taxes, guaranteeing a living wage, and ensuring basic rights for all. Instead, they create the very conditions that put their wealth at greater risk. History shows us—from the storming of the Bastille, to the Paris Commune, to Bloody Sunday in Russia—that such conditions inevitably spark resistance, no matter how much military force is deployed to suppress it.

Even now, the passing of the Big Beautiful Bill is beginning to create class consciousness—even among those who once voted the billionaires into power. For decades, monopoly capitalists have shaped public opinion through control of the press and by scapegoating immigrants and other working-class people. But stripping away Medicaid and Social Security moves beyond propaganda—it is a direct transfer of wealth from the working class to the billionaires. This is making more people realize where the true problem lies.

Meanwhile, the two-party system refuses to raise the pitiful $7.25 minimum wage, raises taxes on working people, cuts public services, and increases military spending for the benefit of war profiteers. The aim of the oligarchy is clear. They want to return the majority of society to a state of modern-day serfdom.

King was right. The only way to address the problems facing our country is to restructure society itself. The first step is to build the type of economy and infrastructure we want. We must create our own Terre Gaillard, just as Juan San Malo and the maroons did in the Greater New Orleans area in the 1780s—an economy based on cooperation, solidarity, and mutual aid.

Our community engagement ride on Monday evening was an exploration of how we can begin this work. It focused on two pillars of restructuring: sustainable transportation and urban gardening.

Commuting by bicycle is a silent protest against the oil oligarchy. Once we reject the decades-old lie—that our streets, lives, and economy must revolve around the automobile—we can step into a future less dependent on fossil fuels. Just as electoral districts are gerrymandered, so are our streets. We’ve been taught that car ownership and status are the ultimate expressions of happiness and the middle-class dream.

In reality, bicycles deliver the very freedom that car ads promise: reduced carbon emissions, a healthier lifestyle, a stronger sense of community, and money saved. For those concerned about sweat, weather, children, and rain, the book How to Live Well Without a Car is a great resource.

The second focus of the ride was cooperative economics—specifically, community-supported agriculture (CSA). After the Second Reconstruction, cooperative farms such as the Freedom Farm Cooperative, New Communities, Inc., and the Poor People’s Cooperative emerged as models of self-reliance.

During our ride, we visited three community gardens in New Orleans that are helping to build a solidarity economy. We learned what is possible, how we can support them, and how we can grow our own network. With a citywide web of urban gardens, we can reclaim food sovereignty and break free from the food deserts imposed on our communities. One garden even had a chicken coop to produce its own eggs. If such models became widespread, and we had collective stores, imagine our ability to respond to price hikes and shortages.

We honor the community members who welcomed us into their spaces. Here’s some guidelines on how to get involved:

Ms. Gloria’s Garden – Active volunteer opportunities every day. Contact for details. Located in the 5th Ward.

Earthseed Community Gardens – Introduced to us by Justine in the 7th Ward. Contact them to volunteer.

Land Back Community Gardens – Introduced to us by Jenna Mae in the 9th Ward. Volunteers meet the first Saturday of each month at 8 a.m.

Let us begin now to create the economy we want to see, working toward Dr. King’s vision of a restructured society. Thank you for riding with us and helping create a critical mass of inspiration to keep riding and building—another world is possible!

- Eric Gabourel