Musée de la Compagnie des Indes: Exploring The Company That Founded New Orleans

New Orleans is a business—When the city was founded in 1718, it was under the auspices of the Company of the West (also known as the Mississippi Company). Before Louis XIV died in 1715, his only legitimate son had already predeceased him. His grandson was the king of Spain, so the only rightful heir to the throne of France was his great-grandson, Louis XV.

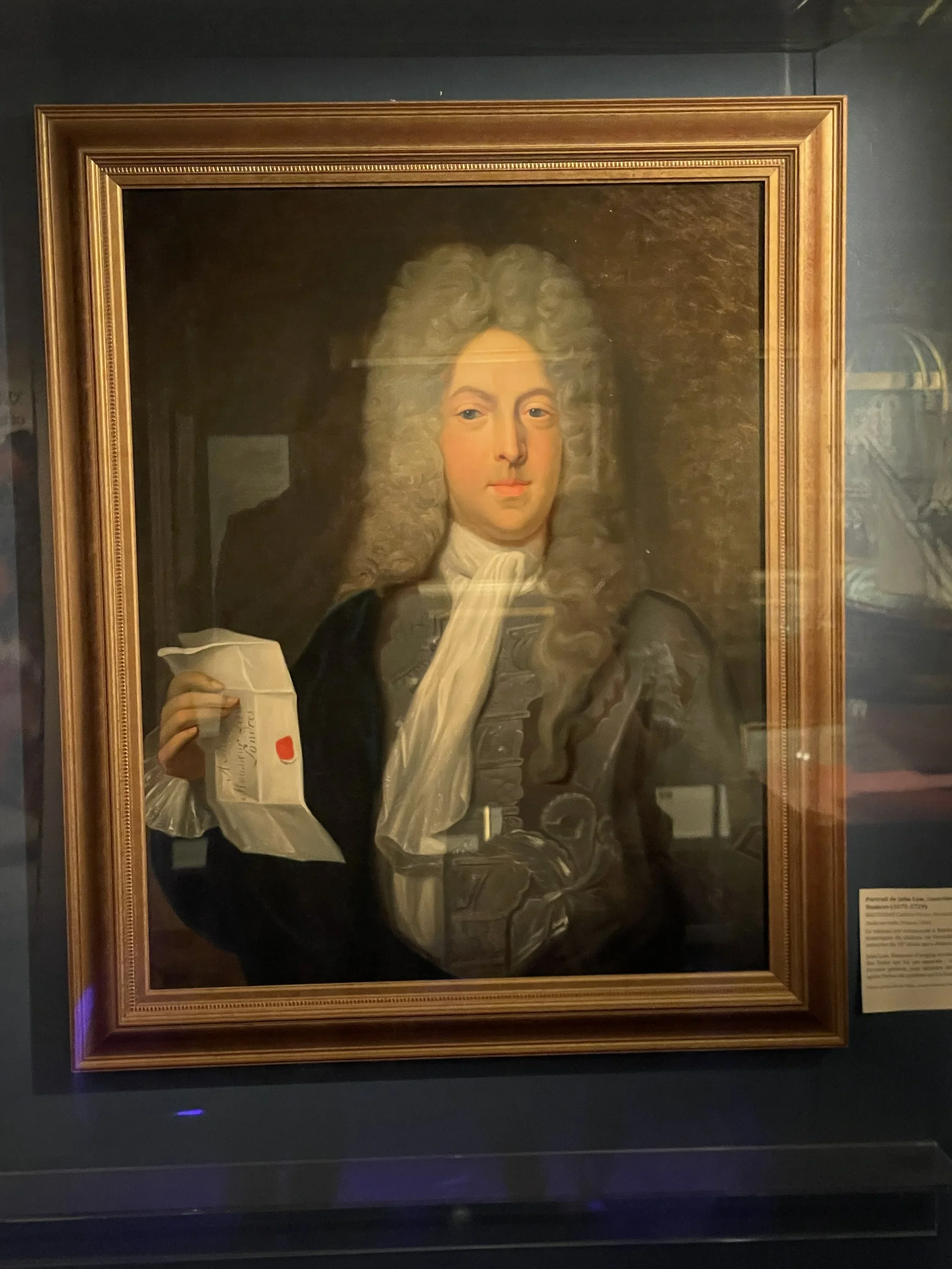

A painting of John Law at the Museum of the East in Lorient, France.

At the time of Louis XIV’s death, Louis XV was only five years old. One couldn’t legally be king until the ripe—or not so ripe—age of thirteen. To serve as regent until Louis XV came of age, Louis XIV appointed his nephew, Philippe II, Duke of Orléans.

Given to the pitfalls of overindulgent pleasure, Philippe did little to improve an economy plagued by war budgets and extravagant royal expenditures. But then came along a most curious Scot, who ended up in Paris after escaping from prison. John Law had landed in a Scottish jail after killing a man in a duel. He had been challenged because he was having an affair with the man's wife.

After being imprisoned for murder, Law escaped and fled to mainland Europe. With a mind like a calculator, he built a fortune counting cards at gambling tables. After working the circuit, he arrived in Paris, where he met the Duke of Orléans in a brothel. He introduced Philippe to the concept of paper currency and its potential for reviving the French economy. Philippe bought into his ideas—hook, line, and sinker. After Law opened the General Bank of France, Philippe eventually appointed him Controller General of Finances for the entire kingdom.

An illustration on display at the museum, depicting people buying shares in John Law’s Mississippi Company on Rue Quincampoix (Paris, France).

Philippe put every financial institution in the kingdom under Law’s control—including the Company of the East Indies. Law was also granted a 25-year concession to establish Louisiana as a lucrative outpost of French colonialism. He turned Louisiana into a stock market scheme, selling shares in the colony on Rue Quincampoix in Paris. Louisiana was marketed as a magical land that could produce crops faster than Jack could grow beanstalks.

Law also oversaw the establishment of Louisiana’s capital, which was named New Orleans in honor of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans. French and German journals of the time were filled with exaggerations and lies about both Louisiana and its capital. But people believed them and began buying shares. Now there was a need to produce actual goods.

This is where the Company of the East Indies came in. After it was incorporated into the Company of the West, Law used it to import enslaved people from its concession in Senegal to produce the goods that would make Louisiana profitable. I recently traveled to Lorient, France, the port where the Company of the East Indies was based. Citadelle Port-Louis, a ruin from the company’s headquarters, now houses the well-curated Museum of the Company of the East.

A model of l’Aurore, a ship used in the French slave trade.

Most of the slave ships departed from the port of Lorient (the city itself is named after the Company of the East—L’Orient means “The East” in English). These ships would travel to the island of Gorée to buy human “cargo,” and then transport those who survived the journey to the Caribbean and to Louisiana.

Many of the goods produced in the colonies were shipped back to Lorient, where the company was based. The fort that houses the museum today was once part of its headquarters. Louisiana produced sugar, rice, and indigo for the metropole. Our sister colony, Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), produced 60% of the coffee consumed in all of Europe. The first coffee consumed in Louisiana in the early 1700s likely came from there or from Martinique. The museum includes exhibits dedicated to both coffee and slavery.

A model of l’Aurore shows the human “cargo” in the ship’s lower compartments.

In the slavery exhibit, there is a model of a slave ship named l’Aurore. I’m not 100% sure, but it may represent the first slave ship used in the Louisiana slave trade. The first slave ship to bring enslaved people to Louisiana was also named l’Aurore, though the museum’s art label doesn’t mention its journey to Louisiana.

Regardless, note the middle passage, with people crammed into the hold. During the transatlantic slave trade, millions died of malnourishment and disease en route to the Americas. This holocaust has become known as the Maafa. The Maafa and the transatlantic slave trade shaped New Orleans. Not only did slave labor produce its wealth, but New Orleans also became the largest domestic slave port in the United States just before the Civil War. The people were sold as commodities alongside the commodities their labor produced.

The economic disparities created by this legacy are still with us. Those who created wealth for both France and Louisiana are still struggling to participate in the prosperity they built.

— Eric Gabourel

The author, Eric Gabourel, in front of la Musée de la Compagnie des Indes in Lorient, France.