From the Gulf States Newsroom: Critical Mass Nola and St. Claude Ave.

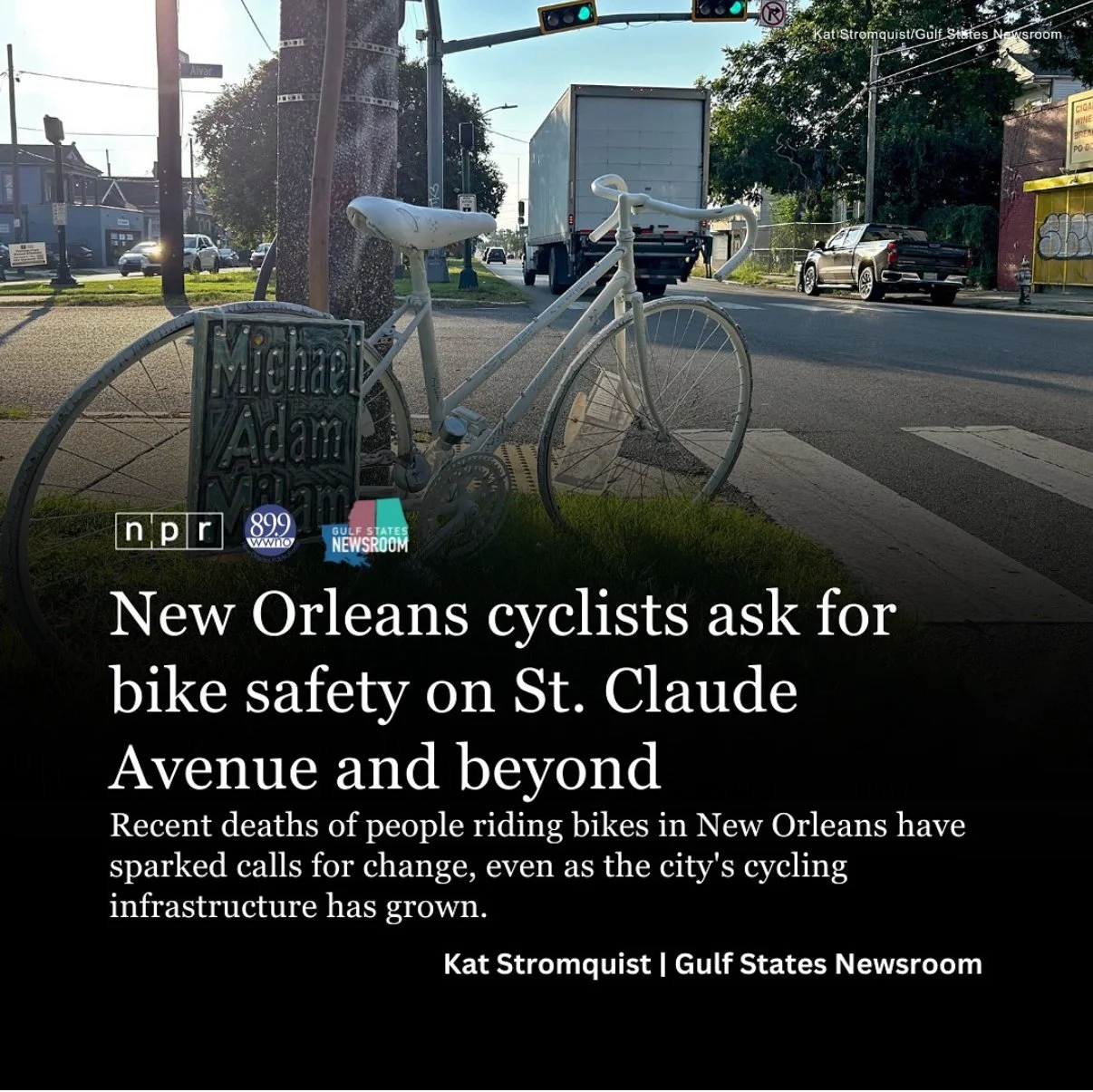

New Orleans journalist Kat Stromquist, writing for Gulf States Newsroom and WWNO, recently published one of the most powerful examinations yet of the deadly crisis facing cyclists in our city and the grassroots struggle to confront it. Her reporting follows the tragedies on St. Claude Avenue this summer, where two cyclists — including Michael Milam, a 36-year-old bartender — were killed within weeks of each other.

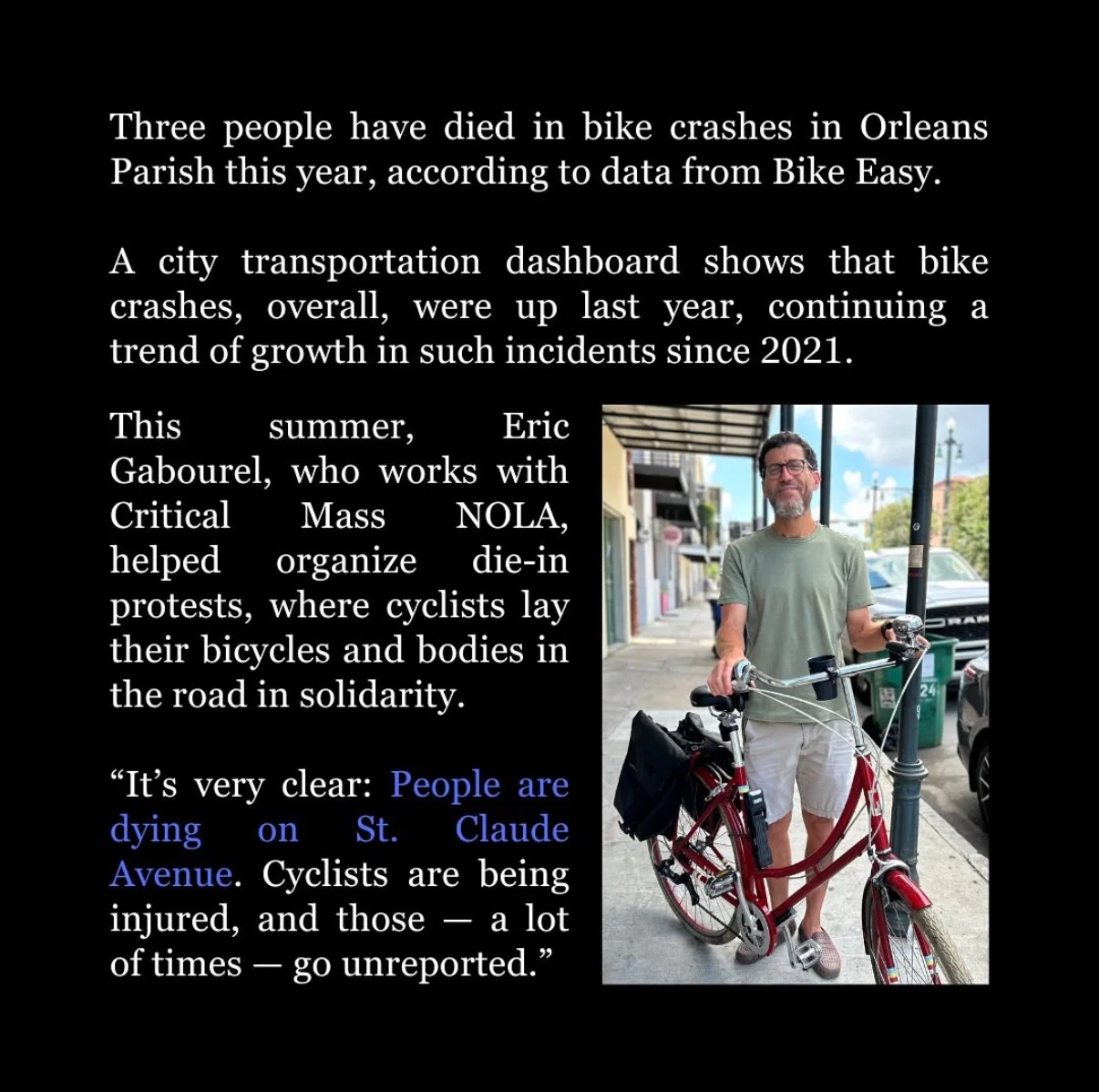

Milam’s death was a hit-and-run. He was left in the street to die, alone. When I spoke to Stromquist, I stressed that these are not isolated events. Another cyclist, 65 year-old Miron Lockett, was killed later that same month on St. Claude. Together, these deaths underscore the brutal truth: our streets are organized around cars and commerce, not human life.

As co-organizer of Critical Mass NOLA, I have long described St. Claude Avenue as a corridor of death. The painted bike lane that runs alongside heavy, high speed traffic is insufficient and dangerous. Cars idle in it, rideshare drivers block it, and trucks barrel past it. In response to this summer’s tragedies, Critical Mass Nola organized die-in protests, where cyclists lay their bodies and bikes in the roadway to dramatize what the state refuses to acknowledge — that blood is the price being paid for car dominance.

The contradictions are plain. New Orleans has the highest percentage of bike commuters of any Southern city. The terrain and street grid make it an ideal cycling city. Yet the infrastructure tells another story. Cyclists are being killed this on the streets of Orleans Parish, and countless injuries go unreported. While the City Council has passed a resolution calling on the state Department of Transportation and Development (DOTD) to study St. Claude, the road remains primarily a state-managed freight corridor — LA-46 — that serves the port and trucking industry before it serves the people who live and ride here.

That is why Critical Mass Nola continues to demand protected bike lanes — lanes physically separated from traffic by curbs, parked cars, or barriers. Paint is not protection. Across the developed world, these designs are proven and affordable, yet in New Orleans they are treated as luxuries. The refusal to implement them is not just a technical oversight; it is a political choice that values capital and commerce over working-class lives.

Since Katrina, the bikeway network in New Orleans has grown from just 7 miles to more than 150. That growth reflects a mass desire for something better. A city where people can move freely without a car. But as Stromquist shows, progress is fragile. Lanes often “drop you off” into danger, projects for neighborhoods like New Orleans East are quietly defunded, and every gain is undermined by the overwhelming dominance of cars and trucks.

For CMN, the struggle on St. Claude represents more than a fight for safer bike lanes. It is about whose lives matter in this city. Are we willing to build a transportation system that allows parents to commute by bike with their children safely to school, or will we continue sacrificing our neighbors to the machinery of profit and speed?

The answer is not yet written. But I know this much—cyclists in New Orleans are organizing. We ride, we protest, we mourn, and we refuse to be silent. Thanks to Kat Stromquist’s reporting, our struggle is no longer invisible. What happens on St. Claude will shape the future of this city — whether it continues to serve capital, or whether it finally begins to serve the people.

Listen and Read Kat Stormquist’s story here.

—Eric Gabourel

Keep up with our movement on instagram.