Bulbancha Forever: Colonial Origins, Indigenous Resistance, and the Revolutionary Struggle for Liberation

This National Indigenous Peoples Day we honor and lift up our Native comrades in recognition that La Nouvelle Orléans (New Orleans/Nola) is an imposed man on Bulbancha.

Today Critical Mass Nola is going to celebrate a European religious icon (@feteghisallo); but we do so in reverence of those that were here before us. In recognition of our status as colonial settlers, Critical Mass Nola stands in solidarity with all sovereignty and justice movements waged by our Indigenous comrades.

Please follow, share, and partner with @nanihbvlbancha@bvlbanchaliberationradio @bvlbanchacollective the @united_houma_nation…and all other local Indigenous movements.

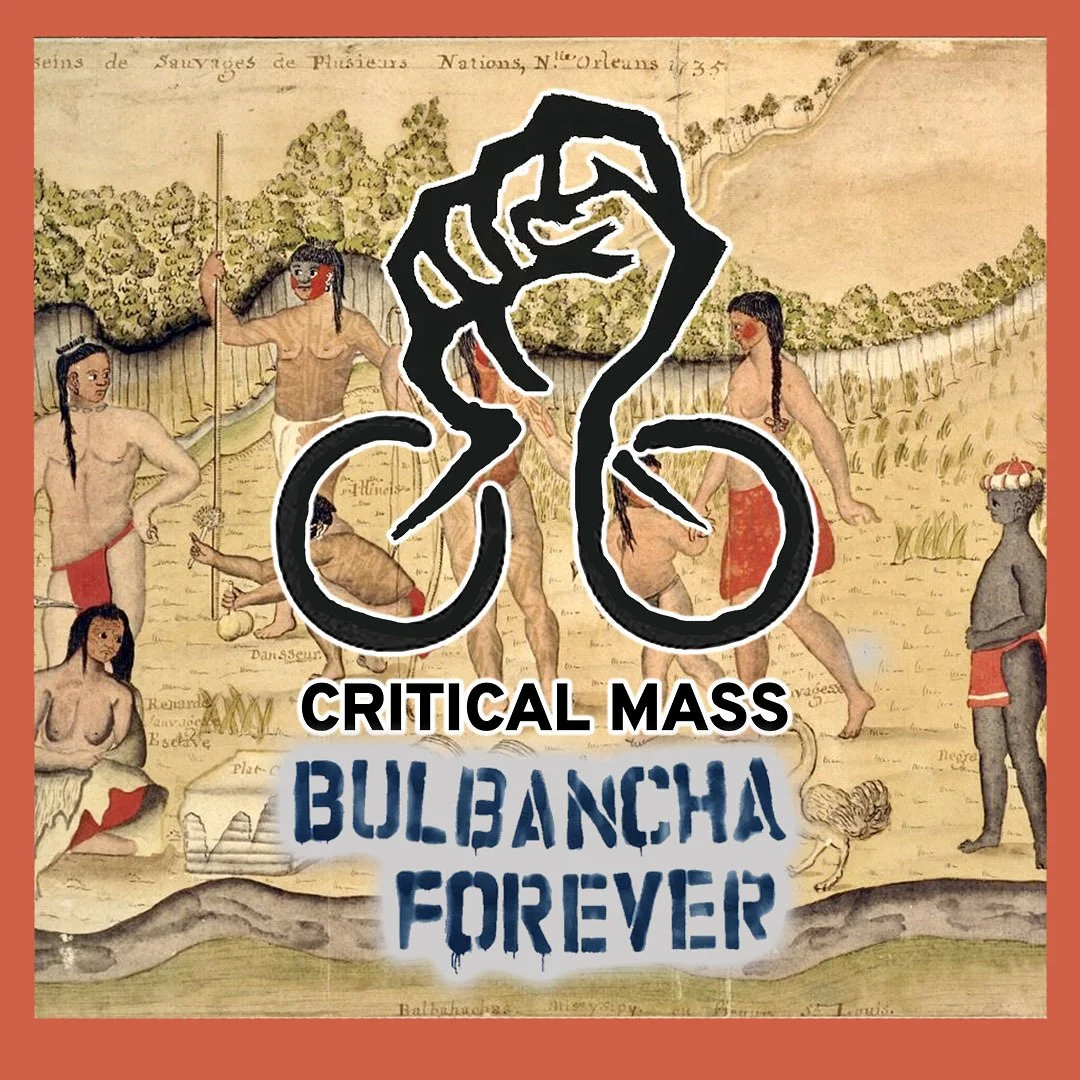

The image accompanying this reflection is a painting of Native and African people in New Orleans, painted in 1735 by Alexandre de Batz. If you zoom in on the bottom of the painting, De Batz lists the Indigenous name of the city as Balbahachas. Modern linguists have corrected his spelling to Bvlbancha—“place of many tongues.” It was here, among a network of Indigenous nations, that European colonization violently imposed itself, renaming, enslaving, and commodifying what had once been a communal world.

From Papal Bulls to the Gulf South: La Salle and the Seizure of Bulbancha

It was under the shadow of the Doctrine of Discovery that French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, erected a cross at the mouth of the Mississippi River in 1682 and claimed the entirety of the river basin for France, naming it La Louisiane. This act was not merely symbolic—it was a moment of enclosure. The land, the waterways, and the Indigenous nations who sustained them were all converted into property, subordinated to the French crown under the spiritual authority of Rome.

Alexandre de Batz, Desseins de Sauvages de Plusieurs Nations (1735). The painting depicts Native people in New Orleans in 1735. De Batz lists the Indigenous name of the city as Balbahachas at the bottom of the painting. Modern linguists have corrected his spelling to Bvlbancha—“place of many tongues.”

Here, the theological mandate of the papal bulls met the logic of capital accumulation. The Mississippi Valley became a new frontier for mercantilism and extraction, paving the way for the plantation economy that would follow. The expropriation of Indigenous land and the enslavement of African labor became the twin pillars of capitalist development in the Gulf South.

In the centuries that followed, this logic expanded—from plantation to petrochemical corridor, from riverfront to refinery, from colonization to climate catastrophe. The same class forces that justified conquest in the 17th century now justify the burning of the planet in the 21st.

The Doctrine of Discovery and the Theft of the World

More than five centuries after it was first proclaimed, the Vatican issued a formal statement on March 30, 2023, repudiating the Euro-supremacist Doctrine of Discovery.

Composed of papal decrees between 1452 and 1497 (Dum Diversas, Romanus Pontifex, Inter Caetera), the doctrine gave Christian conquerors the divine right to claim all lands not occupied by Christians, enslave their inhabitants, and seize their wealth “in the name of God.” It became the theological and quasi-legal foundation for global colonization, genocide, and the capitalist world system.

The papal repudiation—won through decades of Indigenous resistance across the Americas—marks a symbolic step forward. Yet the U.S. Supreme Court continues to uphold this colonial doctrine as an integral part of U.S. law.

In Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), Chief Justice John Marshall declared that Native peoples held only a “right of occupancy” to their lands, while absolute title belonged to the “discovering” European powers and their successor state, the United States. This legal fiction made Indigenous sovereignty impossible within the capitalist property system.

Nearly two centuries later, in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation (2005), Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg invoked this same doctrine in a ruling against the Oneida Nation, a people of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, who had sought to reassert sovereignty over lands guaranteed to them by the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua. Ginsburg’s majority opinion reaffirmed that, under the Doctrine of Discovery, “title to the land occupied by Indians when the colonists arrived became vested in the sovereign.”

Even in McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020), the Supreme Court’s nominal victory for Native sovereignty, the same colonial premise remained intact—that Indigenous rights exist only insofar as Congress allows them. The system still assumes that Native sovereignty is a delegated privilege, not an inherent right.

Bulbancha and the Struggle for Liberation

Marx wrote that “capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.” Louisiana’s soil is soaked in both. Yet the resistance of Indigenous and African peoples also runs deep here—maroons in the swamps, Native nations persisting despite centuries of forced displacement, and new generations demanding an end to the fossil-fuel economy that grew out of those same colonial relations.

For Critical Mass NOLA, acknowledging Bulbancha is not a symbolic gesture but an act of revolutionary remembrance. To ride through these streets is to move through layers of history—each one marked by struggle. The bicycle, humble yet transformative, represents a form of mobility rooted not in domination but in cooperation, ecology, and communal life.

We ride not only to decentralize the automobile but to decentralize capital itself—to reclaim the commons, to liberate movement from fossil dependency, to build an infrastructure for the people and the planet.

Revolutionary Solidarity

As we honor Indigenous Peoples Day, we do so understanding that decolonization is not a metaphor—it is a material process. It demands the abolition of private property, the return of land, and the dismantling of the state structures that perpetuate colonial domination.

Critical Mass NOLA stands in solidarity with all movements of sovereignty and justice—Indigenous, Black, working-class, and ecological. We ride for the liberation of the land, for the memory of Bulbancha, for the day when the city is no longer a monument to conquest but a commune of free people.

Bulbancha Forever!